“We should be making boys boys,” she said in a skirling Scottish accent thick as porridge, “not turning them into girls!”

She was encouraging me to write about the massive molly-coddling of young people these days, especially boys, who, seemingly, are barred at every turn from doing things boys have done for centuries – in the process earning good, proud scars on their arms and legs and heads and hands and feet. And also in that self-same process they have learned a great deal about doing practical things safely.

“But,” said the wee Scottish lady, herself the mother of two, “can you say it in a way that will encourage mothers to allow the boys to do it – to get out there and be boys and play in the mud and have fun and climb trees and build huts in the silage stack …”

And she recounted how her young son had horrified his grandma by embedding a piece of ripe meat in the toe of a stocking and using it to successfully fish for eels in a local drain.

For those who can’t figure how that works, you need to understand that eels have a mouth full of slightly back-pointing tiny teeth, and grabbing a mouthful of stocking-wrapped meat ensures they’re well and truly snared.

Half a century ago, when such things were not quite so potently frowned on, we caught koura by a similar, though somewhat more robust method.

A long, green, feathery frond of manuka branch had the guts of a rabbit or possum tied into the middle of it, and the frond was lowered onto the clear stony or sandy bottom of a slow-moving stream or lake edge, and left for half an hour or so just after dark.

A quick flick over it with a good torch soon showed whether the catch was set – a dozen or so sparkling little diamond eyes indicated the presence of a bunch of feeding koura, and the branch was quickly pulled ashore and shaken.

Out fell the koura, trapped and prevented from their natural fast reversal out of trouble because the spines on their legs became entangled in the fine twigs of the branches.

I’m reliably informed they tasted excellent after a few minutes in a billy of boiling water.

Just the other day, by coincidence, I saw three young boys on a sloping roadside paddock out in front of a farm house.

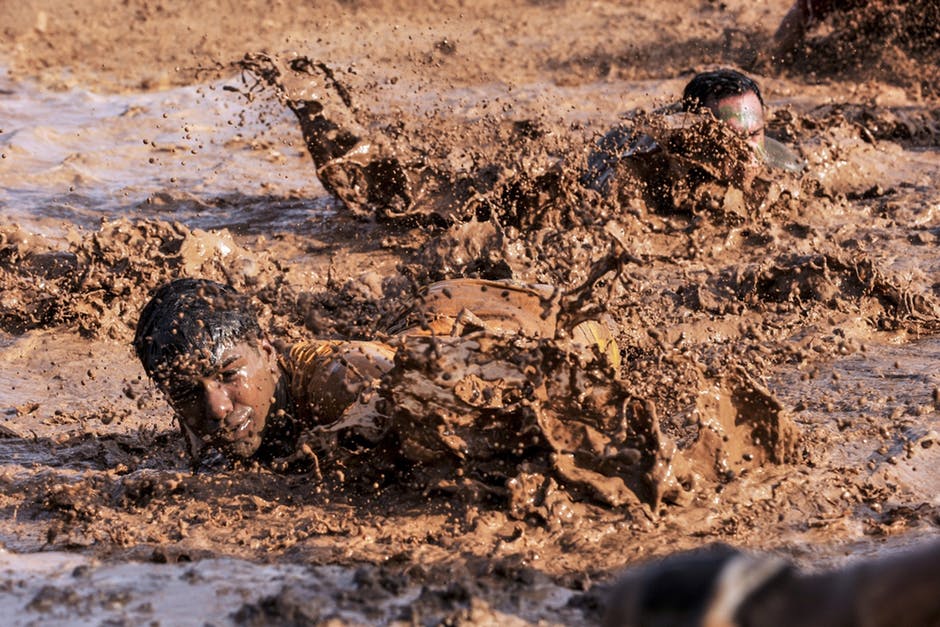

With the ground sodden and well chewed down by stock, these lads had made themselves a mud-slide, and were working off all that surplus energy youngsters have by hammering downhill through the ever-widening slide on their knees, laughing like crazy as one or the other wiped out and spun or rolled crazily, or nose-dived head-first into the slush as one or other knee dug in.

Those boys were all sodden balls of sludge, and no doubt one or several mothers would not have been entirely happy at the clean-up prospects. But I’d bet good dollars that those boys will remember such times when they’re sober, upright citizens in 40 years from now, and maybe will smile secretly to themselves.

We did some very crazy things as kids: climbing precariously out to the wobbling ends of high branches; building a huge shanghai and trying to land a rock on the neighbour’s cowshed; playing with matches and fire-crackers in the hay paddock; making manuka bows that fired bamboo arrows tipped with sharpened four-inch nails.

We got barberry thorns in our feet, and stone bruises, and torn and bleeding shins, and the odd dig-bite, and major scabs on our knees and elbows, and bee stings, and bumps and bruises and bangs and scrapes and scratches. And the occasional deep cut from the IXL or Mercator pocketknives we always carried.

And we winced and sometimes cried when our mother daubed Iodine on cuts and grazes, and dug out thorns and prickles, and occasionally removed stitches from healed cuts.

I think the only thing she ever told us not to do was go down to the river – it was too fast and dangerous.

Otherwise, the farm, and those of our neighbours, was our playground, and there was little of that countryside we didn’t know closely.

Adventure is what helps make boys into men of worth and depth and character, because they’ve grown up with the knowledge that boundaries can and should be pushed, and that there are safe ways to push boundaries, that there are sometimes risks that need evaluation, and that there are also very stupid ways to do things if you choose.

Having adventures provides the chance to learn how to differentiate between safe pushing, risky pushing, and complete idiocy.

Getting outside into the great outdoors, whether it’s a farm paddock behind the house, a gully in the heart of the city, or the open tops of the massive Fiordland country, can give us the chance to face up to challenges.

In one of the endless bunch of hunting books that continues to hit the bookshop shelves, philosopher and hunter Greig Caigou very cogently notes: “It is this uncertainty (of being outdoors) that give us the potential for experiencing risk, and taking risk is a key to growth. Being out in the natural environment while on hunting trips does provide risks, but also provides a great adventure environment in which to grow.”

And he is absolutely right.

Regrettably, more and more boys are growing up in towns and cities where they have little chance to enjoy the scary exhilaration of barreling out of control down a mud-slide; or go birds-nesting and have the robbed eggs break in their mouth; or make a shanghai and try to bring down one of a mob of flighting duck; or sit around a campfire deep in the bush and listen to the moreporks and on the morrow learn how to safely cross a river – or to make the judgement call not to cross it just now because the current is too strong.

Adventure such as gutting your first deer under the tuition of an experienced hunter, and then having to carry it out yourself provides that hard edge of reality too – pulling the trigger is the clean, easy bit; removing the still-steaming gralloch, then putting the bony carcass on your shoulders and carrying it for an hour or three through rough country to your camp needs stamina, determination and a realisation that you can do things you didn’t think you could. And that it’s useful to think through the consequences of what you’re proposing to do before you do it.

As Caigou points out: “There should be room for that vital ingredient of ‘adventure’, with enough uncertainly to cause anxious moments and yet to feel the exhilaration of success.”

And, of course, it would help bring to back the fun of being a boy.

Read more from Kinsgley Field here

Kingsley is a columnist with the Waikato Times in Hamilton.

Join the Discussion

Type out your comment here:

You must be logged in to post a comment.